The Unexpected Quiet: Are Small Galaxies Rewriting Black Hole Theory?

For decades, the prevailing wisdom in astrophysics has been that most, if not all, galaxies harbor a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at their center. But a groundbreaking new study, leveraging over 20 years of data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, is challenging this assumption. Researchers have found that a surprisingly small percentage – around 30% – of dwarf galaxies appear to contain these cosmic behemoths. This discovery isn’t just a statistical anomaly; it’s forcing scientists to rethink how SMBHs form and evolve.

The X-Ray Signature of Hidden Giants

The detection of SMBHs relies heavily on observing the intense X-ray emissions produced when matter spirals into the black hole’s event horizon. Larger galaxies consistently exhibit these bright X-ray sources, confirming the presence of a central SMBH. However, smaller galaxies often lack this telltale signature. Over 90% of galaxies comparable in size to our Milky Way are believed to host SMBHs. But galaxies with masses less than 3 billion times that of our Sun rarely show the bright X-ray emissions expected.

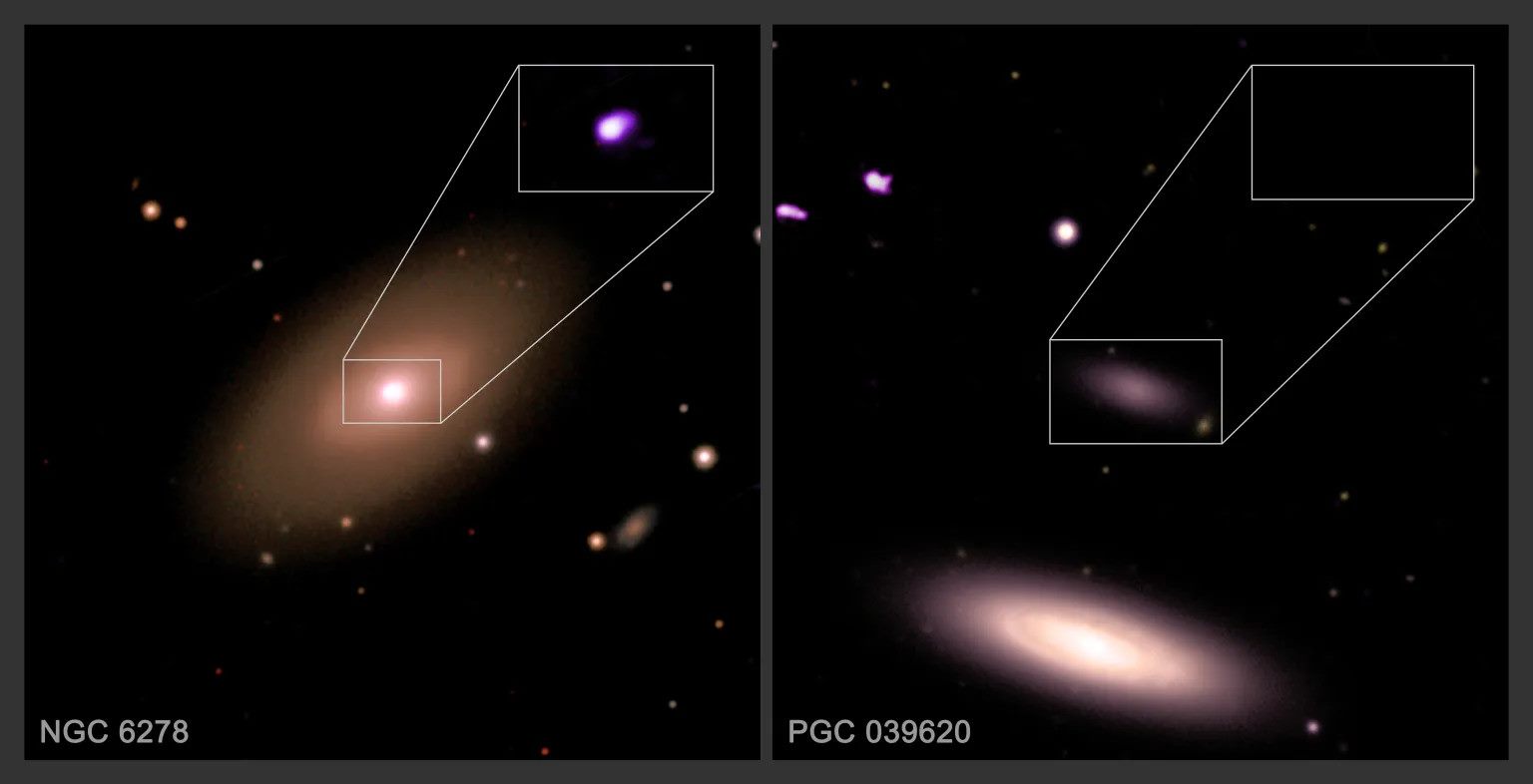

NGC 6278 and PGC 039620, selected from a sample of 1,600 galaxies, were used to probe the existence of supermassive black holes. The results indicate that small galaxies are less likely to contain SMBHs than large galaxies. Many smaller galaxies, like PGC 03620, likely lack a central SMBH. (Source: X-ray: NASA / CXC / SAO / F. Zou et al.; Optical: SDSS; Image processing: NASA / CXC / SAO / N. Wolk)

Two Possible Explanations: Missing Black Holes or Dim Signals?

The research team initially considered two possibilities. The first was that smaller galaxies simply have a lower proportion of SMBHs compared to larger galaxies. The second was that the X-ray emissions from black holes in these smaller galaxies are too faint for Chandra to detect. Their analysis of the Chandra data strongly supports the first explanation. While smaller black holes are expected to accrete less gas and therefore emit weaker X-rays, the observed lack of X-ray sources was far greater than anticipated.

Implications for Black Hole Formation Theories

This finding has significant implications for our understanding of SMBH formation. Currently, two main theories dominate the field. One proposes that SMBHs form directly from the collapse of massive gas clouds, initially possessing masses of thousands of solar masses. The other suggests that they grow from smaller “seed” black holes formed from the collapse of massive stars. The new research lends support to the direct collapse theory. If seed black holes were common in small galaxies, we would expect to see a similar proportion of SMBHs in both large and small galaxies. The observed discrepancy suggests that the conditions necessary for direct collapse are more prevalent in larger galaxies.

The Future of Gravitational Wave Astronomy

The reduced number of SMBHs in dwarf galaxies also has implications for the future of gravitational wave astronomy. The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), scheduled for launch in the coming years, will be able to detect gravitational waves produced by the mergers of black holes. If dwarf galaxies contain fewer black holes, the rate of these mergers – and therefore the number of detectable gravitational wave events – will be lower than previously predicted. Furthermore, the frequency of tidal disruption events, where a black hole tears apart a star, will also likely decrease.

Beyond Chandra: The Next Generation of Observations

This research highlights the importance of continued observations with advanced telescopes. Future X-ray observatories, with greater sensitivity and resolution, will be crucial for detecting faint X-ray emissions from SMBHs in dwarf galaxies. Combined with data from optical and radio telescopes, these observations will provide a more complete picture of the distribution and evolution of black holes throughout the universe. The James Webb Space Telescope, with its infrared capabilities, may also play a role in identifying obscured black holes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- What is a supermassive black hole? A supermassive black hole is a black hole with a mass millions or billions of times that of our Sun, typically found at the center of galaxies.

- How do scientists detect black holes? Black holes are detected by observing their gravitational effects on surrounding matter and by detecting the X-rays emitted when matter falls into them.

- Why are dwarf galaxies important for studying black holes? Dwarf galaxies provide a unique opportunity to study the early stages of galaxy and black hole evolution.

- What is the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA)? LISA is a planned space-based gravitational wave observatory that will detect low-frequency gravitational waves, including those produced by merging supermassive black holes.

Pro Tip: Keep an eye on upcoming data releases from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). Its wide-field imaging capabilities will revolutionize our understanding of the distribution of galaxies and black holes.

Explore further research on arXiv and learn more about NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory here.

(This article is authorized for reprint by the Taipei Astronomical Museum; Featured image source: Pixabay)